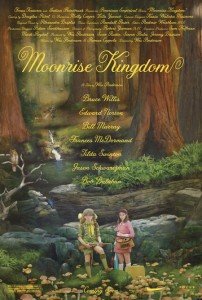

Wes Anderson’s seventh film has arrived with a fresh but pleasantly familiar set of style, theme, and attitude. Moonrise Kingdom, like many of Anderson’s films, has a storybook form that allows us to return to youthful moments such as children and pre-teens having adult sentiments and acting on them.

Wes Anderson’s seventh film has arrived with a fresh but pleasantly familiar set of style, theme, and attitude. Moonrise Kingdom, like many of Anderson’s films, has a storybook form that allows us to return to youthful moments such as children and pre-teens having adult sentiments and acting on them.

Khaki scout Sam Shakusky (Jared Gilman) has resigned from the Khaki Scouts and left the camp with Scout Master Randy (Edward Norton) and the rest of his scouts looking for him. Meanwhile, Suzy Bishop (Kara Hayward), has also left her home, leaving her father Walt (Bill Murray) and her mother Laura (Frances McDormand) on edge regarding her whereabouts. After perusing Suzy’s year-long correspondence with Sam, Island Police Captain Sharp (Bruce Willis) is called upon to trail them and return them to their home.

Moonrise Kingdom opens with an exposition that is in the classic Anderson style. Benjamin Britten’s “The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra” plays over the opening titles and a visual introduction to the Bishop household. This scene is reminiscent of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou where there is a smooth, parallel tour of the submarine via a cross-cut. The film’s narrator and Greek chorus is provided by Bob Balaban, who explains the island’s climate, geography, history, and the eventual storm that sets the film’s third act in motion. Here, Anderson is introducing important locations by dissecting and deconstructing them, making it more accessible for the spectator to consume. Sam also uses this device to present his attention to detail as a Khaki Scout by taking inventory of his and Suzy’s affects as they run away. It explains his excellence in preparedness as a scout, and utilizing resources to provide for the two as they continue their exile.

The storm is an essential part of the film. Noye’s Fludde, an opera also by Britten, is referred to early in the film as Sam first meets Suzy as she prepares for her role as a bird. Moonrise Kingdom uses Noah’s Flood, and the global myth of the Great Flood in general, to unite or reunite opposites who have an affinity towards each other, as well as cleanse.

The film’s storybook nature is no accident, as Anderson has used this form in all his films. The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic, and Fantastic Mr. Fox all make use of this narrative form especially, allowing for adult themes to be presented in a way that is reminiscent of the innocence of children’s or young adult literature. Suzy is even reading young adult fiction, sometimes out loud to calm and comfort others.

Sam and Suzy’s exile in Moonrise Kingdom is indicative of Margot and Richey in The Royal Tenenbaums, where the two run away and hide in the Museum of Natural History. Also, this merges two important French New Wave directors styles and films together. Sam and Suzy summon the on-the-run eccentricity of Jean-Luc Goddard’s Vivre sa vie, especially on the beach where the two strip away their inhibitions for the first times in their lives.

It is criminal to ignore the performances in this film, especially with an ensemble cast like this. Again, Anderson has assembled a collective of old and new talents, finding time to balance each characters’ backstories and weaving a narrative that will eventually lead to charming metamorphoses. Newcomers Hayward and Gilman channel the stoneface seriousness necessary to carry out their characters’ adult motivations while remaining true to their child-like curiosity. Both of them will have room to grow from this experience, but their roles in Moonrise Kingdom will be forever enshrined them in American film history, as did Jason Schwatzman’s role in Rushmore.

It is criminal to ignore the performances in this film, especially with an ensemble cast like this. Again, Anderson has assembled a collective of old and new talents, finding time to balance each characters’ backstories and weaving a narrative that will eventually lead to charming metamorphoses. Newcomers Hayward and Gilman channel the stoneface seriousness necessary to carry out their characters’ adult motivations while remaining true to their child-like curiosity. Both of them will have room to grow from this experience, but their roles in Moonrise Kingdom will be forever enshrined them in American film history, as did Jason Schwatzman’s role in Rushmore.

McDormand and Murray portray a couple on the edge of their relationship, but still finishing each other's sentences when it comes to legal issues. Willis’s role as a police officer is a dark send-up of typecast roles of his past. Even Tilda Swinton as Social Services (seriously, that's her name) has the cold demeanor that is not only a common role for her, but a perfect performance, especially for an Anderson film. Norton plays a role that is so drastically different from his past. The loneliness that his character portrays is hidden by his consistent instructions and power tripping on his scouts.

Moonrise Kingdom shows enormous growth for Anderson. His successful stop-motion animation outing with Fantastic Mr. Fox has given him a boost in his own storytelling talent. It shows in this film, as the most basic enjoyment of this film revolves an isolated island community attempting to capture two pre-teens who have proclaimed their love for each other, meanwhile, each individual character has their own narrative where they yearn for the same type of love. It is a theme that is accessible and relatable.

On a more complex level, the film uses a plethora of references to film history, symphonic music, and literature, all the while using iconography that links the film to the warmth and comfort of a wondrous young adult novel. These symbols and their deconstruction presents a post-modernity that Anderson is known for.

Last, Anderson has mostly abandoned his typical use of the Futura typeset and font and replacing it with an elegant cursive font. This change signals Anderson’s arrival as a filmmaker who has augmented his systematic auteur style with an innovative angle, putting him ahead of his imitators. Moonrise Kingdom has replay value thanks to its charm, reliability, and inherent love story that is rather irresistible.

Aaron Weiss is a freelance film critic and web developer and has recently graduated with a Master's in Cinema Studies from the Savannah College of Art and Design. This Moonrise Kingdom movie review was originally published at CinemaFunk, a website dedicated to movie reviews and film criticism that specializes in independent and art film.

Support Bristow Beat - Donate Today!