The video game industry has become a $25 billion dollar industry, but its inherent features share all but one element with cinema, how the spectator interacts with the medium. That does not matter in Wreck-It Ralph, because the fundamental struggle is one that the main protagonist shares with the majority of humans: depression from exclusion and existentialism.

The video game industry has become a $25 billion dollar industry, but its inherent features share all but one element with cinema, how the spectator interacts with the medium. That does not matter in Wreck-It Ralph, because the fundamental struggle is one that the main protagonist shares with the majority of humans: depression from exclusion and existentialism.

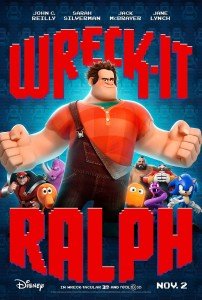

For nearly thirty years, Wreck-It Ralph (John C. Reilly) has wrecked a lone standing building in Niceland, only to have it repaired by Fix-It Felix (Jack McBrayer) almost instantaneously, saving the residents who cast Ralph off a building. Ralph has played this part without accolades and has begun to sink into depression he joins Bad-Anon, a support group for video game villains, where he expresses his loss of interest in being the bad guy. When a young girl inserts a quarter to play around of Fix-It Felix Jr., Ralph is nowhere to be seen. Ralph has instead snuck into Hero’s Duty in order to earn the Hero’s Medal, which he believes will give him the accolade to continue with his mundane digital life, only crash land into Sugar Rush, a candy-based kart racing game.

Wreck-It Ralph is the next in line for an CGI-animated retro love affair with beloved franchise characters. Similar to how Who Framed Roger Rabbit? brought together cartoon and animated characters from disparate film studios, Wreck-It Ralph features a vast combination of video game characters across universes. The film utilizes the same concept of Toy Story: What do video game characters do when the lights go down? Apparently, they have lives similar to ours by celebrating success or even contemplating the roles their occupation has in their lives.

These existential themes of exclusion do not just fall over Ralph, but also unintentionally over Vanellope von Schweetz (Sarah Silverman) who lives a rambunctious existence as an outcaste glitch in Sugar Rush. Vanellope and Ralph make a pact that Ralph will receive the Hero’s Medal from Hero’s Duty if he helps Vanellope win a race. Ralph of course learns that the Hero’s Medal will not truly cure him of his moment of funk, thus the medal becomes a red herring, and his struggle becomes non-materialistic. The existentialism is supported by the law of video games that if a video game character dies outside their own game they cannot regenerate. If only video game players understood this law outside real life, perhaps they would place more emphasis on, as the closing speech in Bad-Anon meetings profoundly proclaims, taking things a day at a time. Then again, Ralph may align with a certain audience who feels the same disenchantment with doing the same occupation for long periods of time.

Fix-It Felix and Wreck-It Ralph are binary opposites (yes, even I can do puns), and these oppositions exists everywhere in the film. Felix, whose mission is to find and fix Ralph’s egregious absence from the game, falls for Sergeant Tamora Jean Calhoun (Jane Lynch), whose home video game is the one that Ralph wrecked. The vast differences between Hero’s Journey and Sugar Rush is too obvious to note, but both games tend to procure tenacious antagonists. One as a totalitarian king who oversees the races, and the other is an ever-multiplying swarm of alien-insects.

The most incredible aspect of the film is the appropriate casting. The lovable cynicism of Reilly’s vocal gruff is accurate to Ralph’s mannerisms. McBrayer, whose Southern bumpkin persona of smiling politely despite the inner pain is executed lovingly to Felix, who is beloved by the residents of Niceland. Jane Lynch relays her butch feminism to a female sergeant who represents the military industrial complex that exists within first-person shooters, and Silverman re-configures her Jewish potty-mouth for the adorable pre-teen Vanellope. Of course the vocal talents do not end there, like any grand event from Disney, there are dozens of house-hold names who have lent their talents.

Late in Wreck-It Ralph it is revealed what the film is about: Retro. The word that describes the embracing, modern impact of a nostalgic object or time. The film specifically captures this ideal in the same fashion as other animated films have in the past in order to entertain both children and adults who exists on different intellectual planes, while re-fueling franchises for planned obsolesces. Early in the film we are given a short backstory regarding Turbo of Turbo Time, a racing game that lost spectatorship to a newer, more advanced game.

Now that Disney has Pixar under its own banner, the massive conglomerate can now release two large-budget CGI animated films a year, which allows them to devour the sought-after multi-demographic animated niche. Then again, Disney did it right by having Rich Moore, whose animated credits reach from The Simpsons, Futurama, and The Critic, to helm the joystick of this cabinet. Wreck-It Ralph revels in its own video game idolatry, but is too convoluted to maintain any sort of central focus, perhaps like a video game.

In the Disney/Pixar tradition, Paperman is a short animated film that precedes Wreck-It Ralph.

Aaron Weiss writes film reviews for CinemaFunk.com where this review of Wreck-It Ralph was originally published. Aaron resides in Valrico, FL.

Support Bristow Beat - Donate Today!