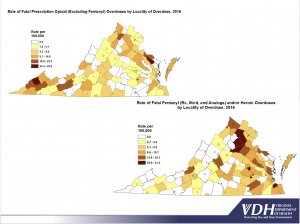

Powerpoint slide shows the rate of fatalities per county. Top: overdoes from opioid prescriptions excluding fentanyl in 2016. Below: rate of fatal fentanyl and heroin overdoes.

Powerpoint slide shows the rate of fatalities per county. Top: overdoes from opioid prescriptions excluding fentanyl in 2016. Below: rate of fatal fentanyl and heroin overdoes.Submitted by Prince William County Government

There's a nationwide opioid epidemic that's killing people, and Prince William County is not immune to the problem.

The opioid epidemic and how it's impacting the county was recently discussed at a community event at Forest Park High School entitled "Opioid Epidemic: Let's Talk About It!"

According to 1st Sgt. Kenneth Hulsey with the county's Narcotics Task Force, the problem started to emerge in the county in 2012 when the Police Department documented an increase in drug confiscations, overdoses and overdose deaths from opioids.

Opioids act in the brain to produce euphoria, and they fall into two categories: prescription painkillers, like morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, tramadol and methadone; and illicit drugs, like heroin.

Hulsey told the audience that there were 498 overdoses in Prince William County in 2016 with 52 of those overdoses resulting in death. In 2012, there were 37 deaths in the county caused by opioid overdoses. "We're seeing increases in overdoses each year," he said.

Virginia State Health Commissioner Dr. Marissa Levine spoke at the event and said that opioid addiction often starts with prescription drugs, but quickly progresses to heroin use since heroin is cheaper and easier to get.

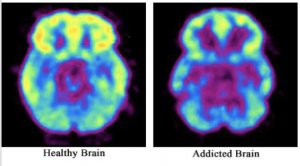

The image shows how the brain of a drug addict is changed over time.

The image shows how the brain of a drug addict is changed over time.To complicate the problem, Levine said, drugs such as fentanyl and carfentanil have been introduced into the equation. Fentanyl is commonly used for pain management of stage four cancer and is 10 times more potent than heroin. Carfentanil is a synthetic opioid that was originally designed to be used by veterinarians as a large animal tranquilizer and is 100 times stronger than fentanyl.

According to Hulsey, drug dealers have started to lace heroin with carfentanil and fentanyl, which cause overdoses because people don't know the strength of the heroin they're buying.

Hulsey said that carfentanil can kill in doses no larger than a grain of salt, and it can be absorbed through the skin. People who are not addicts and have no tolerance to opioids can die by coming into contact with carfentanil dust on clothes, furniture or other area where the dust might collect.

Surprisingly, Hulsey said, the drugs that cause overdose deaths are attractive to drug users. "Addicts want to use the strongest product possible, so if it killed somebody and they know it killed that person, they want to acquire that drug. They think it's in its purest form and they want to use it."

In response to the problem, Levine issued a Declaration of Public Health Emergency on behalf of the Virginia Department of Health in November 2016. The declaration recognized that opioid addiction exists in the Commonwealth and that it represents a danger to the health and safety of Virginians. "There really is no place in Virginia that's not affected," she said.

Hulsey echoed her statement noting that, since many people become addicted through prescription medications, all groups of society are left vulnerable. "This problem hits all ages, hits all socioeconomic backgrounds… We've seen older folks and younger folks. It doesn't matter — black, white, Spanish, Asian. It doesn't matter."

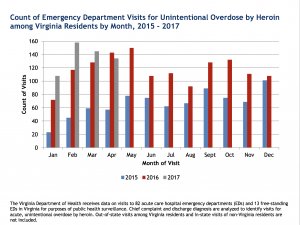

Bar graph shows the number of emergency room response to incidents of unintentional heroin overdoses has risen in Virginia from 2015-17.

Bar graph shows the number of emergency room response to incidents of unintentional heroin overdoses has risen in Virginia from 2015-17.Levine said the only way to fight the problem is for the community to come together. Law enforcement can't do the job alone, she said. "Our law enforcement officials have been saying for years now that we can't arrest our way out of this issue, and I agree with that. Law enforcement has a role in interdiction for illicit drugs coming into our community in the first place. Physicians have a critical responsibility not to write those prescriptions in a manner that is getting people addicted."

Levine said local leadership, community service boards, non-profits and citizens need to come together to work on the problem. "We can't just do one thing and expect that this will go away. It's going to take a concerted effort. Right now, because the community piece is so significant, we've organized at the state to support what you're doing here and what's happening around different parts of Virginia. Our most critical activity is what's happening here today, the community coming together. Everything we're doing at the state level is just to support the local level."

One of the things Prince William County officials have done is to establish the Rapid Reentry Program. The program enlists a number of county agencies, including the Police, Fire and Rescue, Social Services, Community Services, Criminal Justice Services, Commonwealth Attorney's, the Adult and Juvenile Detention Centers, Prince William County Schools and Virginia Department of Health to battle the opioid epidemic by running education and awareness programs. The program aims to help people who are using opioids receive treatment as quickly as possible.

Prince William Supervisor Jeanine Lawson spoke at the event on behalf of the Board of County Supervisors and said raising awareness and facing the problem head-on was critical.

"We have unanimously taken a strong interest in the opioid epidemic that we're seeing across the country, not just here in Virginia; and I'm so thankful that we are here tonight discussing this. This is exactly what we need to do… to start talking about it comprehensively."

Visit the Virginia Department of Health's website for more information.

Powerpoint available via the Prince William County, Communications Specialist, Office of Executive Management, or email stacyshaw@bristowbeat.com.

Support Bristow Beat - Donate Today!